A Blueprint for an Elite Education

Montaigne's antidote to modern schooling...

Modern education is failing. Children are increasingly taught by screens instead of books and teachers — and many find themselves wondering what a solid education should really look like.

But the question of how to go about educating the youth is not a new one.

In Plato’s Republic, Socrates addresses the education of the youth in his distinctive, edgy style, much to the ire of the prevailing political powers at the time. He believed education should begin by instilling virtue, building a moral character, and preparing young citizens to live harmoniously with the larger society.

While Socrates laid the foundation for the philosophy of education, he said little about the practice of education, except through his demonstrations of what we now call the Socratic method. However, the question of effective education has not laid dormant since. Many would take up Socrates’ philosophy of education and extend it to practical methods.

One of the greatest minds of Western philosophy, Michel Eyquem de Montaigne, gave particular attention to the problem of education by reflecting on the good and the bad of his own education.

Here’s what he had to say about real education and how it compares to today’s methods of schooling...

Reminder: you can support us and get tons of members-only content for a few dollars per month 👇

- Two new, full-length articles every single week

- Access the entire archive of useful knowledge that built the West

- Get actionable principles from history to help navigate modernity

- Support independent, educational content that reaches millions

A Childhood of Learning

The famous “Montaigne” of 16th century France — a wealthy nobleman and Renaissance philosopher — was educated a little differently than most.

His father, though living amongst the highest members of French society, desired his son to understand the experience of the commoners in their region. Thus, Montaigne’s infant years were spent with a peasant family to “draw the boy close to the people, and to the life conditions of the people”, where young Montaigne grew to live first without all the wealth and privilege of his family’s status.

After a dose of living with common folk and returning back to his father’s chateau, he was immersed in Latin, as everyone — servants too — only spoke Latin with him. Montaigne later laments that his command of Latin gained at home was ruined by the formal courses at university. Effective education didn’t require formal institutions.

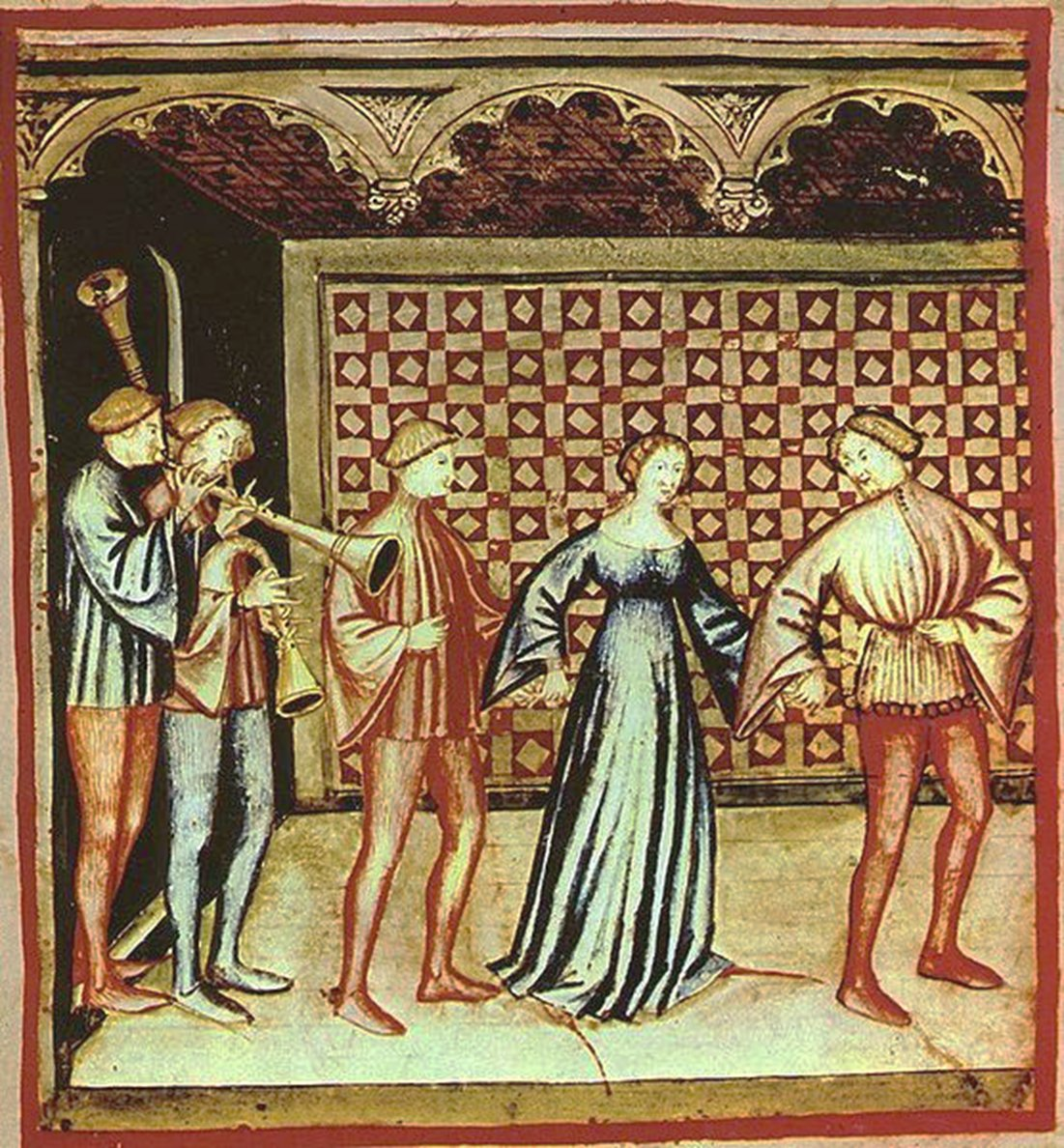

Further, his alarm clock was live music — played on a different instrument each morning. Music was an organic part of his daily habit, and culture was integrated into his daily life.

Montaigne’s childhood education was broad, holistic, and integrated into his daily habits — a far cry from the style of education today which emphasizes programs, schedules, and rigid agendas.

But boarding school and law school interrupted this idyllic education, which shaped his later writings on schooling in his famous Essays. Here, he called the education of children the most important difficulty of human science. They are the future of humanity, after all.

The Aim of Education

In a nod to Socrates, Montaigne wrote that the first aim of education is virtue. Modern schools, he complains, only “furnish our heads with knowledge, but not a word of judgment and virtue.”

Without virtue, knowledge can be dangerous. Only after learning what is wise and good can one pursue the various sciences, which in Montaigne’s day were logic, physics, geometry and rhetoric. Otherwise, we end up with unethical mad scientists, manipulative strategists, and sophists. Modern schools say nothing of virtue and appear to operate purely as utilitarian institutions.

But Montaigne’s issues with the educational system ran even deeper. He believed in a natural integration of education in life — by living and doing, not by droll curricula:

“‘Tis not a soul, ’tis not a body that we are training up, but a man, and we ought not to divide him.”

Modern schools do the opposite of Montaigne's advice…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Atlas Press to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.

Already have an account? Sign in