Should America Be a Monarchy?

Why Hamilton's plan wasn't so crazy

In 1787 Alexander Hamilton argued that the United States should resemble an elective monarchy, featuring a strong national leader elected for life. It might sound like heresy to modern Americans, but his idea had some merit — and exposes a shortcoming of modern governments.

Although Hamilton enjoys pride of place among historical figures as a founding father of the United States, his support for centralized government and a powerful executive has tarnished his image today. This isn’t surprising considering he referred to the British governmental system — which America fought a war to disentangle itself from — as the “best in the world.”

Despite his blemished reputation, Hamilton advocated for “good government” which pursued longevity and stability, characteristics sorely needed in today's political climate.

Though far from perfect, his original plan for America sheds light on a key weakness of many of today’s political systems…

Reminder: you can support us and get tons of members-only content for a few dollars per month 👇

- Two full-length, new articles every single week

- Access to the entire archive of useful knowledge that built the West

- Get actionable principles from history to help navigate modernity

- Support independent, educational content that reaches millions

Hamilton’s King

Hamilton gave an impassioned, six-hour-long speech at the constitutional convention laying out his plan for the government and a powerful executive head. Despite his zeal, though, it was resoundingly voted down in favor of the system the U.S. has today.

But what did Hamilton advocate for exactly?

Sympathetic to Britain’s strong monarchy, Hamilton proposed a system that was similar to his former allegiance’s government. But unlike the British monarchy, where power was transferred via bloodline, Hamilton’s leader — referred to as the national “governor” — would be an elected figure.

Hamilton lays out his vision for the executive during his speech:

“The supreme Executive authority of the United States to be vested in a Governor, to be elected to serve during good behavior; the election to be made by Electors chosen by the people in the Election Districts aforesaid.”

Essentially, the governor would retain power for life as long as misconduct did not force an impeachment by congress i.e. “to serve during good behavior.” And he would have a broad swathe of powers, including the ability to veto any law, make treaties, and appoint all chief officers of the Departments of Finance, War, Foreign Affairs, etc. Notably, the executive would also appoint state governors, giving him more power than today’s president.

Hamilton’s monarch-like governor would wield enough power domestically to resist foreign influence, while the possibility of impeachment prevented tyranny. It was a balance of incentives, Hamilton envisioned, that ensured a functional, yet limited rule.

Historical Precedent

As a well-educated man, Hamilton drew from history for much of his worldview. Like other founding fathers, he admired the Roman Republic specifically, calling it the “utmost height of human greatness” in the Federalist Papers.

But before Rome was a republic, it was a kingdom with an elective monarch…

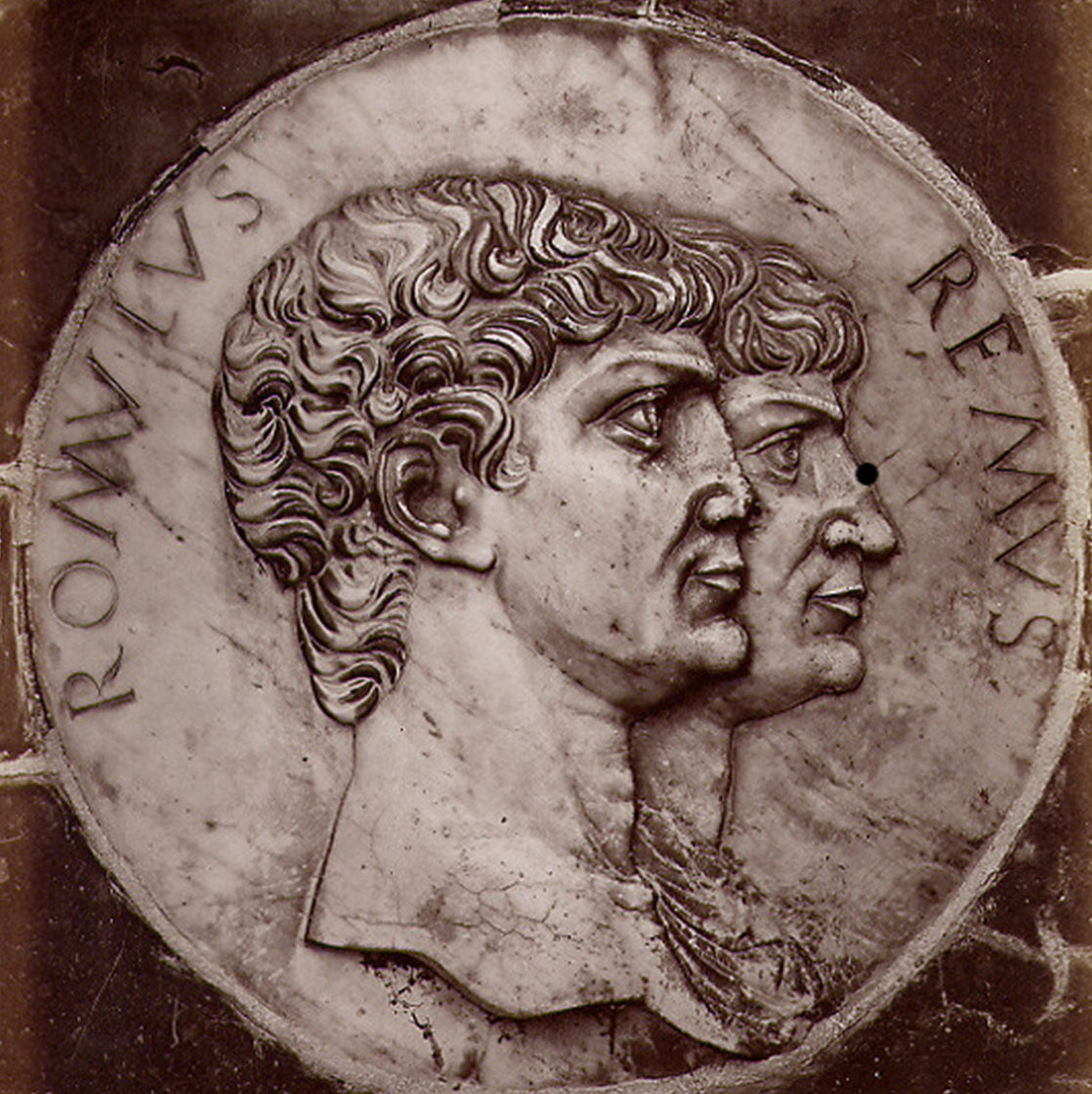

After the first legendary king of Rome Romulus, who took power by killing his brother Remus, monarchs were elected by the Roman people via the Curiate Assembly, who voted on candidates pre-selected by the senate. Though it was ultimately up to the Roman citizenry who became king, the senate held much of the power during the process.

Touted as the successor of Rome, the Holy Roman Empire (HRE), likewise had an elective monarchy. In the HRE the emperor was appointed by a small body of the most powerful princes, or “prince-electors.” Once a leader was selected, the coronation of the emperor took place in either Aachen or Frankfurt, whereupon the prince would become monarch.

The longevity of the Holy Roman Empire, spanning hundreds of years, was a testament to the strength of the system. In fact, it was still intact during the time of the constitutional convention. Though Hamilton critiqued the HRE’s fractured structure, he clearly had no qualms with its monarchical system.

Another contemporary elective monarchy to Hamilton was that of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The Poles held “free elections” upon the death of a monarch, where any Catholic nobleman might be considered for the position.

The Polish system was not as successful as the HRE’s, though, as infighting and even full on battle often occurred between candidates. Historian Norman Davies recorded that "in 1764, when only thirteen electors were killed, it was said that the Election was unusually quiet."

Though uncommon today, elective monarchies were not unheard of when Hamilton made his speech to the constitutional convention in 1787.

Hamilton's plan identified some positives of having a lifelong ruler...

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Atlas Press to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.

Already have an account? Sign in