The Monk Who Shaped Western Education

And kept the flame of civilization alight...

In the 6th century, Western Europe had experienced a recent fall from glory.

Barbarians had deposed the Roman emperor within living memory. Age-old institutions were left in a state of decay. After centuries of cultural dominance, the light of Rome was nearly extinguished.

Literacy was falling, infrastructure crumbling, and the connectedness of the empire fractured. Preserving a millennium-old culture was not a priority for people who merely wanted protection from the next barbarian raid. Chaos was triumphing over order.

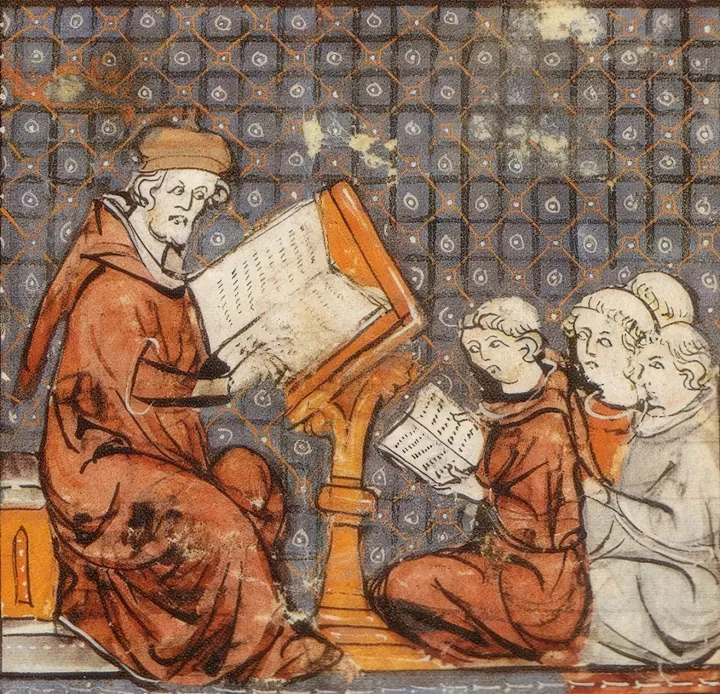

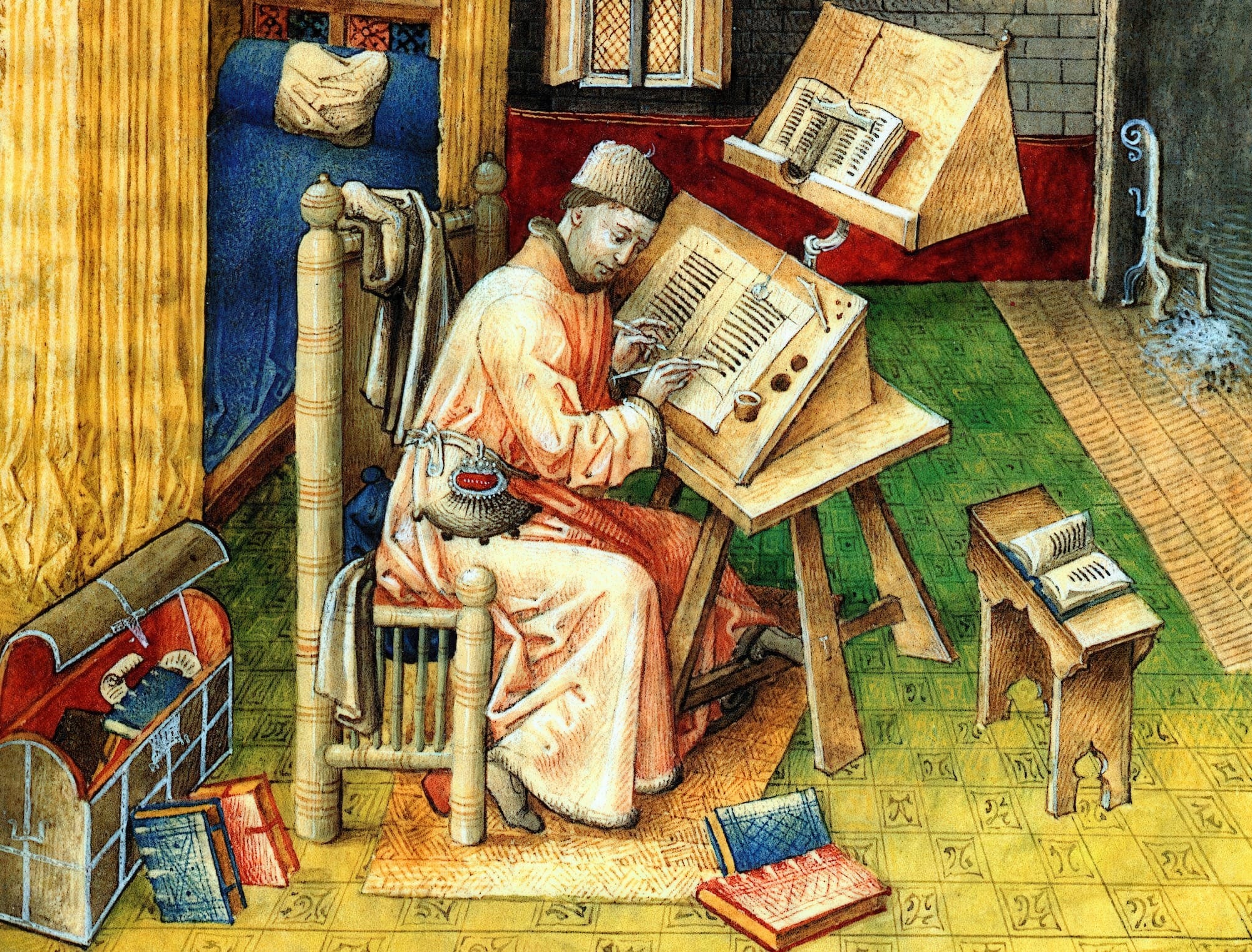

But on the cold stone floors of a monastery nestled in the hills of Calabria, Italy, monks toiled silently, grasping at civilization like a wisp — it would be gone soon if they failed to catch it. Hunched over pieces of parchment, their ink-stained hands formed letters, painstakingly recreating faded texts.

The monks at Vivarium, and the thousands more like them who unceremoniously copied manuscript after manuscript by hand, were just as much heroes of the West as warriors like Charles Martel or King Leonidas.

It was in the quiet confines of a monastery that the West was preserved, and a monk named Cassiodorus created a scheme to ensure its survival for centuries to come...

Reminder: you can support us and get tons of members-only content for a few dollars per month 👇

- Two new, full-length articles every single week

- Access the entire archive of useful knowledge that built the West

- Get actionable principles from history to help navigate modernity

- Support independent, educational content that reaches millions

The Inheritance of Rome

Born in 485 A.D. to a prominent family of government officials, Cassiodorus had no problem rising through the ranks of the Roman political scene. His father reached positions in close vicinity to the emperor as comes rerum privatarum, or “count of the private fortune,” the manager of the emperor’s estates, and finally Praetorian Prefect, the chief administrator to Theodoric the Great. Under the shadow of his father, Cassiodorus soared to equal heights as consul and eventually Praetorian Prefect.

Cassiodorus’s imperial duties, along with his proximity to the greatest minds in the empire, fostered in him an interest for education. His mission was to create a plan for the continuation of Roman education during uncertain times — the chaos of the last half-century left many Romans uneasy about the survival of their cherished institutions.

It is for this reason Cassiodorus looked beyond the emperor’s aid in his educational pursuits; he entreated an even higher power — the Pope — for assistance in conserving Roman culture.

Cassiodorus worked under the guidance of the Pope Agapetus I to establish a collection of Greek and Latin texts that would be used in a new Christian school based in Rome — a beacon of light in an increasingly darkening world.

Though a devout Christian, he found classical texts valuable in their conveyance of transcendent truths. Cassiodorus saw no problem quoting Cicero or Aristotle in a time when pagan authors were often looked at with suspicion.

Unfortunately, his assembly of texts proved fruitless initially, as the school was never built, but Cassiodorus’ work in education wasn’t over, and his life’s work had yet to begin...

An Oasis of Education

It’s impossible to ascertain why Cassiodorus chose to become a monk upon retirement; nonetheless, in 540 he donned the cloth intent on leading a life of simplicity after decades amidst opulence.

On a family estate along the coast of the Ionian Sea, he founded the Benedictine monastery of Vivarium, a monastic school that would ultimately preserve the light of education in the West.

At Vivarium he developed his educational program. He composed a guide, the Institutiones, introducing learners to both scripture and secular works. He believed by studying the texts his guide recommended, a student could obtain a great education without a formal teacher — the texts were the teacher:

“I was moved by divine love to devise for you, with God’s help, these introductory books to take the place of a teacher. Through them I believe that both the textual sequence of Holy Scripture and also a compact account of secular letters may, with God’s grace, be revealed.”

Reading was a transformative act for Cassiodorus. In Institutiones, the monk laid out his framework for a well-rounded education with a focus on reading: first, Christian texts with an initial focus on the Psalms — these could be understood even by untrained readers due to their raw emotional appeal; then, grammar, rhetoric, dialectic, arithmetic, music, geometry, and astronomy.

Later, these subjects would make up the trivium and quadrivium of medieval liberal arts, the basis of Western education.

It should be noted that he encouraged study of secular topics as aides to further understand sacred scripture. Hence, Cassiodorus provided students with a telos for his plan: education should be pursued in order to deepen one’s understanding of God. It was, after all, geared toward monks.

In addition to liberal arts, pupils were encouraged to study medical scripts of ancients like Hippocrates and Galen, making the monks at Vivarium learned in scientific knowledge that was largely unknown to the West at the time.

Letter by Letter

It wasn’t just Cassiodorus’ educational plan that had a profound impact on the preservation of Western culture. He also created a daily regimen for copying ancient manuscripts.

Monks had been copying manuscripts long before Vivarium, notably in the British Isles, but Cassiodorus made it a priority for his school. He obliged all monks to make copying texts a regular practice, widening their availability and ensuring their existence for future generations.

His goal was to safeguard classical history and literature while creating discipline within his monastic school. Cassiodorus' monks along with the multitudes of others in Ireland, England, and Germany ensured the proliferation of previously obscure texts all across Europe and beyond.

And finally, beauty was paramount to Cassiodorus. Having been influenced by Christian Neoplatonism, he believed that beauty and goodness were intertwined.

Therefore his program encouraged the aesthetic enhancement of manuscripts — paint and calligraphy beautified texts and embodied the idea that the knowledge contained within was a treasure. Again, this was not a brand new practice, but Cassiodorus ensured his monks understood their work as not only a disciplinary habit, but an exercise in the preservation of history.

The Preservation of Fire

It’s nearly impossible to overstate Cassiodorus’s impact on the West. His influence within the monastic community contributed to the preservation of many classical and theological texts. We would likely know less of ancient Greece and Rome without Cassiodorus.

Moreover, his scholastic program and insistence that reading was the foundation of a good education laid the groundwork for what is today known as classical education.

Today, we find ourselves entering a second “dark age.” Though we don’t suffer from a lack of information like in 6th century Europe, the West is struggling to remember its roots. We’ve become disinterested and disconnected from the foundational ideas and thinkers that built our civilization.

Our task is not unlike that of Vivarium's monks. Just as they sought to safeguard Roman culture during chaotic times, so too must we strive to protect the riches of our heritage from forces dead set on erasing the Truth, Goodness, and Beauty from the Western canon.

Sir Roger Scruton so aptly reminds us that the preservation of tradition is a vital task:

“We do not merely study the past: we inherit it, and inheritance brings with it not only the rights of ownership, but the duties of trusteeship…Things fought for and died for should not be idly squandered. For they are the property of others, who are not yet born.”