The True Godfather of the Renaissance

And why we owe him our gratitude...

The Renaissance was the culmination of centuries of progress combined with a rediscovery of the classical spirit. Architectural feats like Florence’s Duomo and St. Peter’s Basilica remain recognizable icons of the cultural “rebirth” that swept through Western Europe.

But did you know much of Renaissance architecture was inspired by a single man — one who lived centuries before the great masters were even born?

Artists like Michelangelo, Brunelleschi, and da Vinci were all informed by an obscure Roman engineer who lived more than 1000 years prior. He was their teacher who guided their vision through faded texts — and they honored his genius in their breathtaking creations…

The 16th-century architect Andrea Palladio even called him his “master and guide.” So who was this man that left such an indelible mark on Western Civilization?

Reminder: you can support us and get tons of members-only content for a few dollars per month 👇

- Two full-length, new articles every single week

- Access to the entire archive of useful knowledge that built the West

- Get actionable principles from history to help navigate modernity

- Support independent, educational content that reaches millions

Vitruvius, the Man

The mysterious figure who influenced the great architects of the Renaissance — and those of the Medieval period as well — is known simply as “Vitruvius” as his full name remains unconfirmed.

And like his name, little is known of his life…

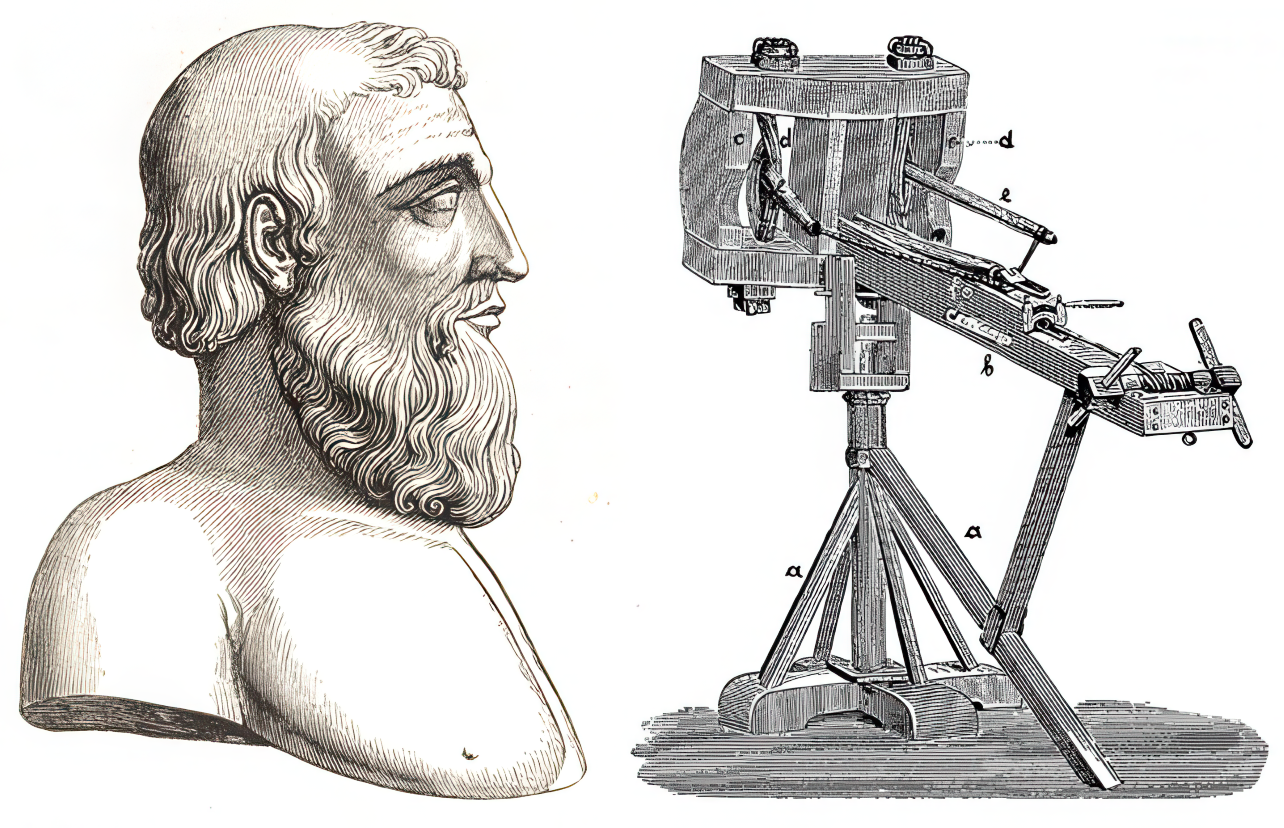

We do know he was a military engineer who served under Julius Caesar in the 1st century BC, specializing in the construction of ballista and scorpio siege engines. It’s theorized he served alongside Caesar’s chief engineer and ally Lucius Cornelius Balbus, who was instrumental in forming the First Triumvirate.

Though impossible to pin down his exact involvement, he likely campaigned in North Africa, Gaul, Hispania, and Pontus near the Black Sea.

But his dynamic military career would be overshadowed by his more creative accomplishments, namely his writings on architecture. Though probably not famous during his own lifetime, shortly after his death he was already well-known for his architectural achievements. The 1st-century Roman engineer Frontinus refers to him simply as "Vitruvius the architect."

How does one go from siege engineering to architecture, though?

Well, Vitruvius was an architect in the way ancient Romans understood the term. Different from the narrow definition we have today, architecture included chemical, civil, and mechanical engineering, as well as construction management, building design, and urban planning.

Vituvius’ broad expertise made him a valuable asset while in the legion, but after he retired he attempted to consolidate his knowledge into a manual for future architects, penning his masterpiece De Architectura, or “On Architecture.”

De Architectura

De Architectura, sometimes referred as The Ten Books on Architecture, is a discourse on architecture dedicated to Augustus Caesar, who may have commissioned the work.

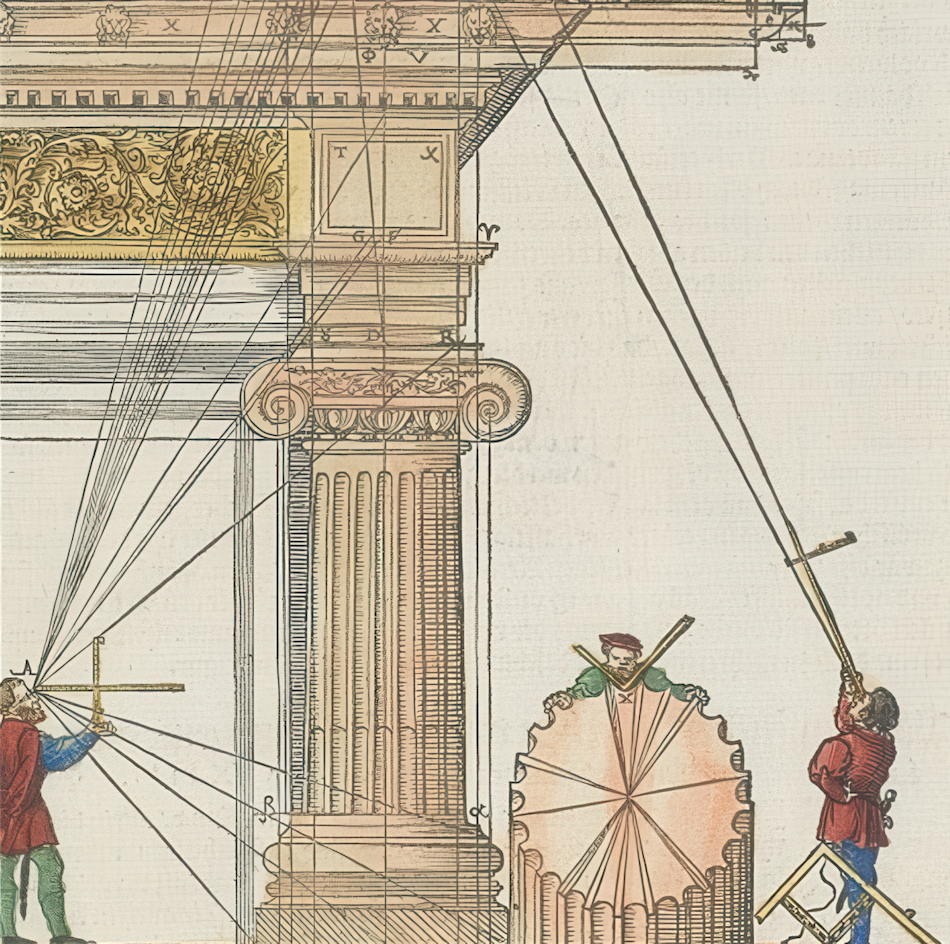

It's perhaps the first work on architectural theory and the only surviving architectural treatise to survive antiquity. The next major work on architecture, Alberti's Ten Books, wasn't written until 1452.

A compilation of Greek as well as Roman architectural advancements, De Architectura contains information about construction techniques, the design of military camps, and structures: aqueducts, mills, baths, harbors, etc. It also discusses various machines used for building these structures like hoists, cranes, and pulleys; and drawing from Vitruvius’ time in the legion, war machines: catapults, ballistae, and siege engines.

Innovative civic inventions are explored like the force pump, dewatering machine, and even central heating, or “hypocaust” — a method of heating that channeled hot air under floors and inside walls of public baths and villas.

But more than simply relaying information, De Architectura established architecture as a field of study, a science…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Atlas Press to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.

Already have an account? Sign in