You read the Narnia books as a child, or had them read to you — the iconic tales that took you beyond the four walls of your bedroom, through the wardrobe in the attic, and into an exhilarating world of magic, prophecy, and mythic beasts.

But at the time you probably weren’t aware of their spiritual depth.

The Chronicles of Narnia weren’t written as mere entertainment for children. They are, of course, profoundly religious stories, created by a devout Anglican, and infused with Christian symbols and ethics.

But C.S. Lewis’s books weren’t written for any straightforward, moralizing purpose, either. Lewis knew that mythic stories are meant to be experienced at a much deeper level, in order to unleash the imagination of the child (or adult) reading it — in a profound sense.

Lewis was trying to awaken something in all of us; something that changed his life not as a child, but as a man in his early 30s.

Here’s what you may have missed in Narnia, and what the author was trying to tell us all along…

Reminder: you can support us and get tons of members-only content for a few dollars per month 👇

Two new, full-length articles every single week

Access the entire archive of useful knowledge that built the West

Get actionable principles from history to help navigate modernity

Support independent, educational content that reaches millions

Christianity in Narnia

The Christian elements of Narnia are glaringly obvious at times, certainly to the adult reader.

Edmund, a stand-in for sin, eats the Turkish Delight before betraying his siblings to the White Witch, seduced by pride. We see the poisonous influence of the serpent on the first man in Genesis, but Edmund can also be read as Judas Iscariot of the New Testament.

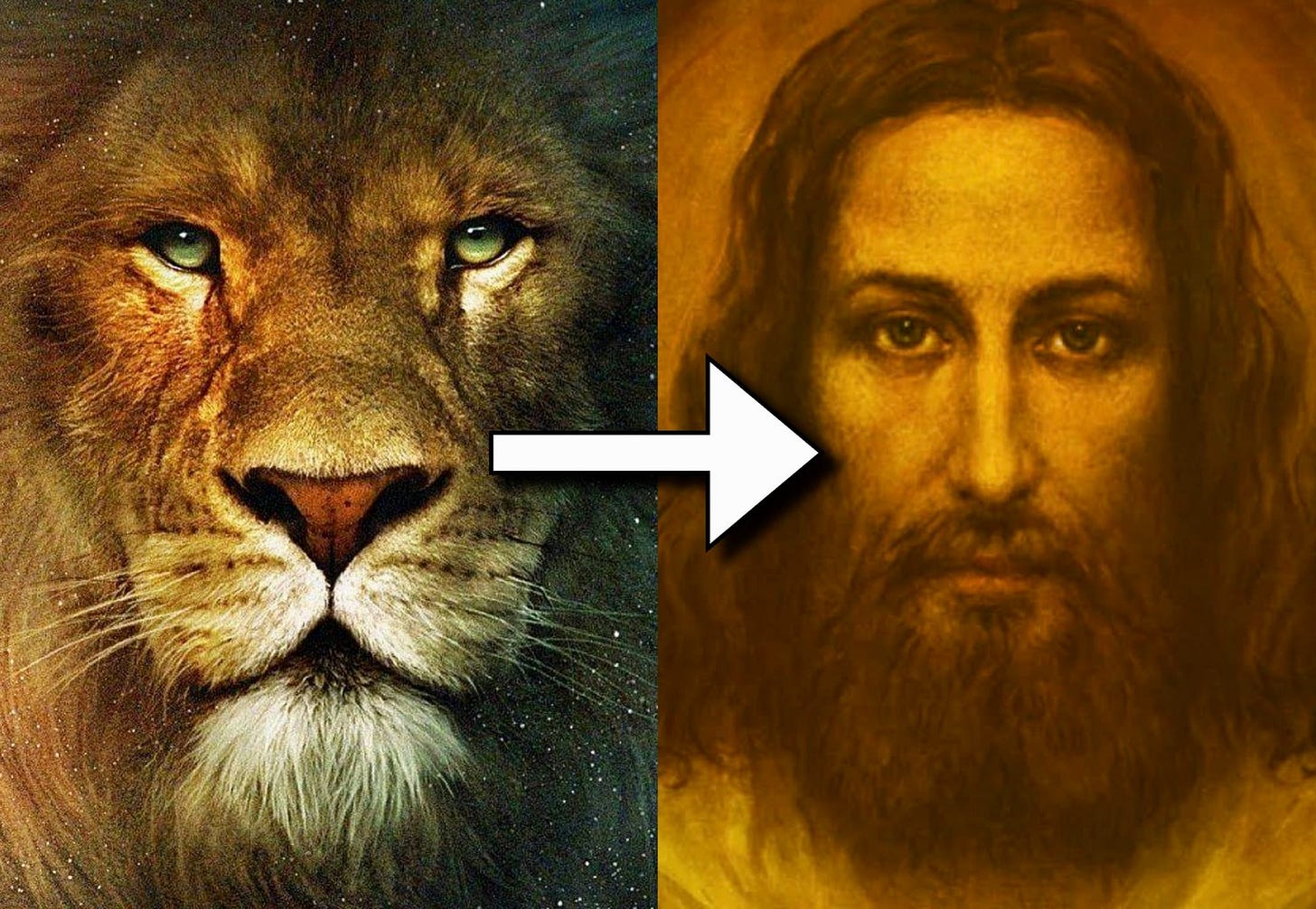

Aslan the Lion comes, as revealed through prophecy, to save Edmund (and all of Narnia) through sacrifice. A great lion wasn’t chosen at random, either — in Revelation, Christ is described as "the Lion of the tribe of Judah."

When Aslan gives himself up to the White Witch, he isn't just killed. He's taunted by a mob, spat on and kicked on the way to the Stone Table (much like Christ at Golgotha). He's later resurrected by a "Deeper Magic", which can reverse death of one who willingly took the place of someone guilty.

Biblical parallels run through the entire series, which even concludes like the New Testament does. In The Last Battle, the "real" Narnia emerges out of the old one's apocalypse, commanded by Aslan, and the corrupted world is replaced by eternal joy.

Death, we learn, is not an ending but another doorway. Aslan now wields judgment, letting some through and condemning others to be "swallowed up in his shadow" — though it isn’t entirely clear where they’ll end up.

Beyond Allegory

Notice, however, that there are no simple, one-to-one allegories. Edmund can be read as Adam, Judas, or sin itself. And unlike Judas, who commits suicide shortly after betraying Jesus, Edmund ultimately repents and finds forgiveness.

Narnia goes beyond simple parallels in other ways, encouraging deeper reflection on the part of the reader. When the Pevensie children grow up, Susan refuses to accept that Narnia was real, and gets lost in the material world: "interested in nothing nowadays except nylons and lipstick and invitations."

The story ends with the children's tragic death in a train wreck, and reunion with Aslan in Narnia. But Susan wasn't with her siblings at the time — she carries on in life, "too keen on being grown-up", and we're left to wonder if she'll make it into Aslan's “Heaven.”

Like his friend and colleague JRR Tolkien, Lewis knew that allegory is a lazy method of storytelling — an unsuitable medium to properly ignite the imagination. He preferred to call his Narnia a "supposal", not an allegory:

"Suppose there were a land like Narnia and that the Son of God, as He became a Man in our world, became a Lion there, what would happen?"

But, through allegory or not, Lewis was relatively unconcerned with making moral or religious arguments in his stories — he was trying to do something much more important.

Above all, he worried that the grind of modernity makes us lose a sense of mystery in ordinary things, whereas mythic stories open us to the idea of reality beyond the material.

Myths, Lewis knew, can do something far greater to the human imagination…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Atlas Press to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.