Why Architecture Shapes Us

What the medievals knew that we forgot

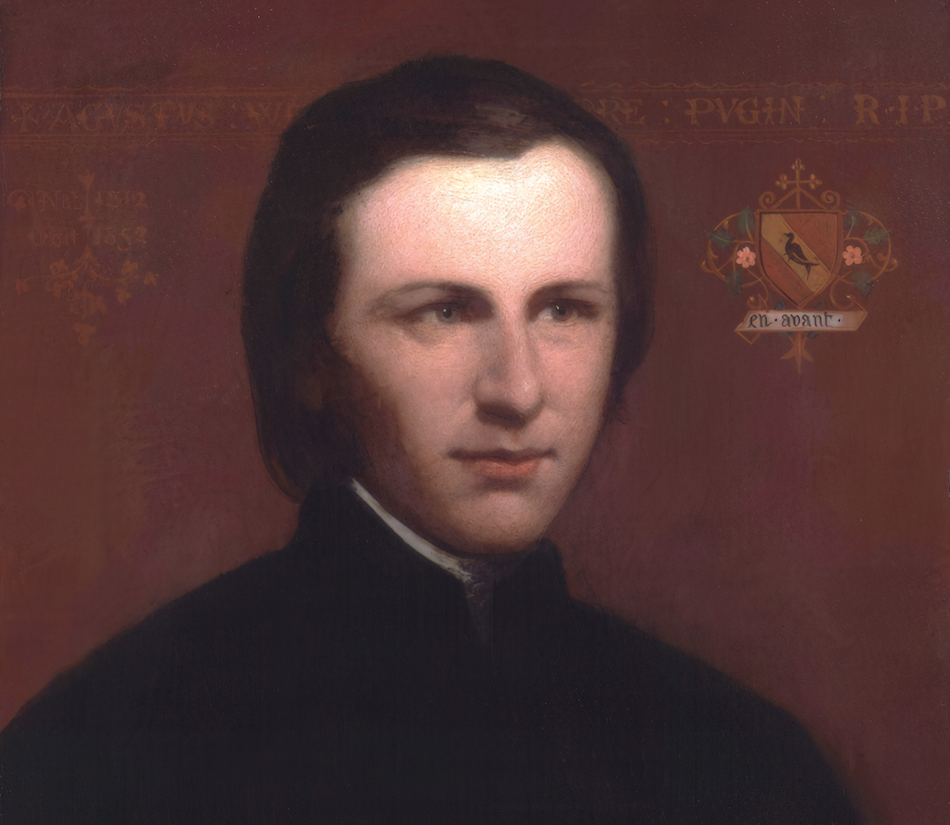

Nineteenth-century architect Augustus Pugin believed architecture could be a moral force — that it could actually shape how people behaved. He envisioned that he could transform society itself by changing its architecture.

But his vision for the future wasn’t new. In fact, it was positively medieval.

Deeply influenced by the culture and art of medieval England, Pugin led an architectural revolution that questioned not just the aesthetics of modernity, but its moral underpinnings, too.

Could good architecture really create a more just society? Would poverty be eliminated if poor houses were built more like religious buildings and less like prisons?

These were the questions Pugin mulled over as he laid the foundations of a forthcoming Christian society. Just maybe, he believed, the best way toward a virtuous future lay in the stone cathedrals of the past...

Reminder: you can support us and get tons of members-only content for a few dollars per month 👇

- Two new, full-length articles every single week

- Access the entire archive of useful knowledge that built the West

- Get actionable principles from history to help navigate modernity

- Support independent, educational content that reaches millions

The Allure of Symbolism

You’ve probably seen Pugin’s impressive Neo-Gothic designs. The interior of the Palace of Westminster and Elizabeth Tower — where Big Ben rests atop — are two of his most famous architectural contributions. They were products of a man who aimed to shape the world both aesthetically and spiritually.

The son of a Presbyterian draftsman, Pugin was inundated by religion and architecture from an early age. Learning his father’s craft as a young man, he began working independently on building designs while wrestling with his faith.

Though devoutly religious, he felt a tension between the stripped-down aesthetics of Protestantism and the complex theological beliefs of Christianity. The Catholic Church, full of pomp and ceremony, was therefore attractive to him in a way that other traditions weren’t.

He eventually converted to Roman Catholicism and his faith greatly influenced his profession, at one point saying:

"I feel perfectly convinced the Roman Catholic Religion is the only one in which the grand and sublime style of church architecture can ever be restored.”

Pugin had a similar feeling for government commissioned projects as he did for protestant churches, in that they sought to build as cheaply as possible, ignoring deep complexities and symbolism.

A Return to Tradition

Pugin’s solution for religious and public architecture was old-fashioned: return to the Gothic style, which had been Christendom’s go-to architectural form throughout the medieval period and focused on conveying religious concepts via simple building materials.

According to Pugin, architecture should not only be functional, but a conduit for revealing the universe’s deepest truths.

In 1836 he penned the work Contrasts arguing for his approach in what is perhaps the first architectural manifesto. Though there had been treatises on building design going back to the ancient Roman engineer Vitruvius, Contrasts was more than a mere technical guide — it offered an entire social and moral framework in which Pugin embedded architectural principles.

Pugin lays out his thesis on the first page:

“On comparing the Architectural Works of the last three centuries with those of the Middle Ages, the wonderful superiority of the latter must strike every attentive observer; and the mind is naturally led to reflect on the causes which have wrought this mighty change, and to endeavor to trace the fall of Architectural taste, from the period of its first decline to the present day…”

Pugin argued that a main element in the return to a more culturally Christian society was to revert to the architectural styles that were present during Christendom’s height. Gothic was most fitting for the Christian ethos, and was the product of a more pure society.

But what made Gothic in particular so attractive to Pugin? Why should it be the preferred architectural style for Christian civilization?

Besides simply being the product of medieval Christian society, the Gothic style conformed with the two “True Principles” of architecture. The principles are as follows:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Atlas Press to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.

Already have an account? Sign in